Rob Cassetti talks about the change in opera when it had competition. Opera was challenged for audiences by the advent of the motion picture. Movies pushed Puccini, for example, to create a big “The Girl of the Golden West” (La fanciulla del West)—creating big, live music that could not be replicated in a movie theater. New technology drove art to change…putting movies on one path, and forcing the traditional medium to change—to keep audiences and to stay relevant. This is the case of illustration—-and the whole schism around traditional media and digital…with digital being poo-poo’ed for not being “real” or legitimate. Technology challenges the status quo—and those either adapt or move aside. Technology may not subsume the traditional—but it does challenge it.

To that, I was plugging away at looking at Ammi Phillips (April 24, 1788 – July 11, 1865) work and discovered in a “no duh” moment that he was working when the first daguerrotypes came on the scene while he was painting (the last 25 years). This creates an interesting time— a blend—when technology, technique, and art purpose can shift due to a new media—a new availability to create images. One can have an oil painting reflecting tradition, wealth, and privilege which would associate you with like people or have a daguerrotype made—showing you “in the moment” with out romanticism, with no softening. A daguerrotype was a singular image like a painting, but very portable and very real. Lively, living breathing people.

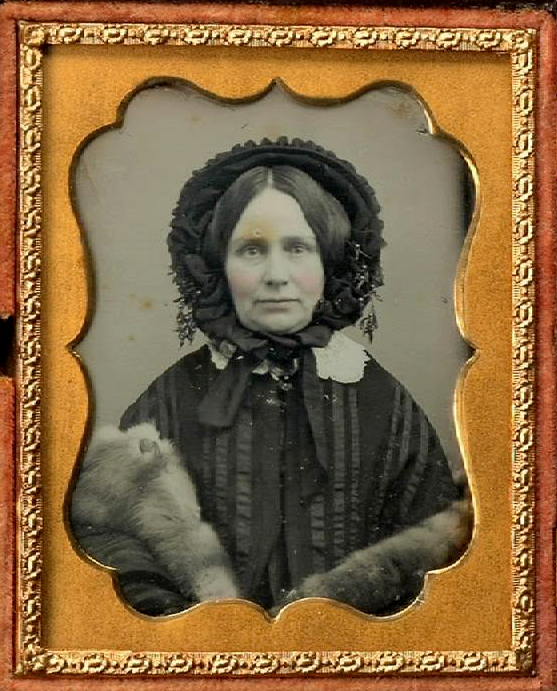

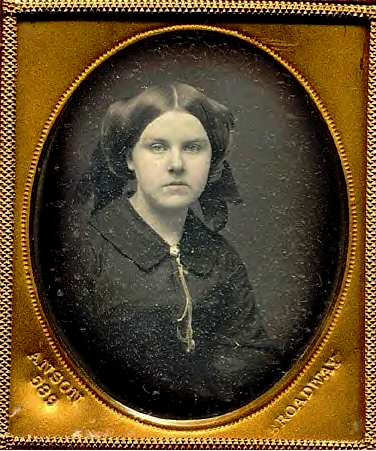

Interestingly, as I looked at the Library of Congress pages— daguerrotypes showed not only living people, but people who smiled, laughed and who had joy in others (pairs of children, groups of sisters). Having a daguerrotype made was something that was a democratic process— with every shape, size, age, race, background and the Library of Congress' collection brought that home while scrolling though all the images. These images show what these people really looked like, how they chose to show themselves—unvarnished—from images of dentists pulling teeth to sweet brothers holding hands.

Clark sisters, five women, three-quarter length portraits, all facing front

Grandmother and aunts of photographer Frances Benjamin Johnston. Digital Id cph 3d02003 //hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3d02003 . Library of Congress Control Number 2004664300

I thought I would go grab a selection of women’s images from the Library of Congress’ online collection to see how a woman might portray herself in a daguerrotype versus the staid portraits that were frozen in time and romanticized by the limner, Ammi Phillips. Could there be clues from a fashion standpoint? layout? design? connection with the viewer? Love Phillips, but let’s just look at what else was happening….even beyond Matthew Brady and his game-changing work and vision.

Here we are (selection was made from images 1840-1849)— and what a group of lovely, real women we have in front of us….women we might know today —work with, socialize except for the clothes that they are wearing and the impossibly time-consuming hair. Many of these wormen are connecting directly with the photographer showing their inner self either with confidence like the awesome Clark sisters, the coy flirtiness of the lady (third row/left), to the insecurity of the picture taking and her youth (center top). These are people who want to be seen, to be captured in the moment—perhaps as a present for a family member, friend or love. These were women with edges, with inperfections, with wit and personality and were not icons of “nice girls”. How did Ammi Phillips respond to this? How did he address this freshness, this change, these portable portraits that were a window into the sitter’s life—many showing similar poses (proper ladies with books, caps) but not romanticized—complete with physical imperfections and souls showing through their eyes.

Technology changed portraiture. People continued to have their portraits painted, but having an option, a more democratic option which was more affordable, portable and a true window into a living person also had it’s appeal. There were couples together, babies together, and families together. There is a daguerrotype of a father and his sons with the bible. There were many, many images of black people—who took advantage of this shift. No conclusions here…just observations on how daguerrotypes touched a much wider swath of people—and captured more of the reality of the time.